That Creative Magic

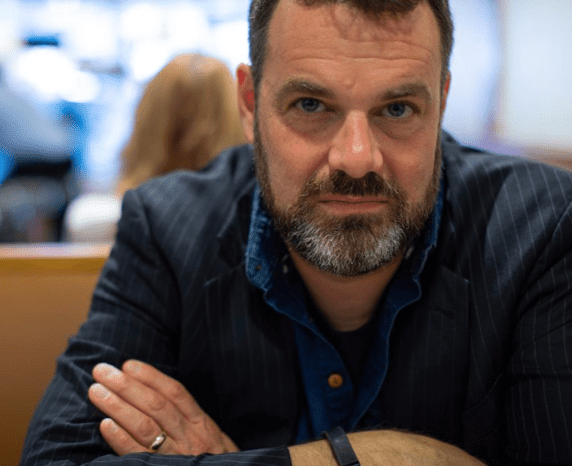

NaNoWriMo’s Grant Faulkner on rediscovering childlike joy, the secret reason so many writers work in cafes, the myth of the lone-wolf scribe…and how the world’s most wildly ambitious writing event is preparing for a November like we’ve never seen before

Creating art isn’t a selfish endeavor. It’s like the quote ‘we change the world by noticing it’. To write is to tell a story that brings light. Creativity is an act of receptivity. It’s an anti-numbing agent.

—Grant Faulkner, National Novel Writing Month Executive Director

Know a teen or middle-grader who has a story to tell? Don’t miss our special, live NaNoWriMo writing challenge for young writers, “Unleash Your Creative Superpowers with National Novel Writing Month,” helmed by stellar YA and middle-grade published authors, October 4th as part of Berkeley #UNBOUND!

Sign up for the portal to get all the details on who, when, and what.

We spoke to author Grant Faulkner of National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo, as it’s known among its hundreds of thousands of devotees across the globe), on an afternoon in which having an entirely “normal” conversation felt a little too surreal for comfort—at least initially. Before we got down to business, we couldn’t help but address the elephant in the room (or, rather, the elephant outside the room’s tightly shut windows): the eerie, occluded jack o’ lantern haze hanging over Berkeley, where Grant lives with his wife and children.

“The best description I’ve heard of [the sky] today is ‘malarial,'” Grant said. “Jaundiced’ also works.'”

Any writer can probably relate: when the circumstances around us are bizarre, fraught, and out of our control, there’s a certain comfort in finding the right descriptor for the chaos. It may not quench the flames, but it provides a certain scaffolding: one that lets us climb to a place where the miasma, at least temporarily, can be contained by our own ability to narrate and name it.

But although Grant may run the world’s largest writing community—NaNoWriMo, launched in 1999, challenges legions of scribes to write a 50,000-word novel every November, has since grown to host real-world writing events all over the world, and has been adapted as a teaching tool in over 6,000 classrooms— he’s the first to recognize that extremity and chaos affect everyone’s creativity differently.

“That became clear in November 2016,” he recounts. “When Trump won, a lot of us [at NaNoWriMo] were caught off guard by that, and we didn’t how how that would impact people. What we found out was that a lot of people just quit writing in 2016. They were traumatized, and for a lot of people it’s impossible to write through trauma. It’s paralyzing.”

This year, NaNoWriMo is facing an unprecedented November. Not only is it the first NaNoWriMo taking place during a pandemic, with everyday routines massively disrupted and many people living increasingly isolated lives, but it’ll be unfolding in the midst of yet another contentious election: one that, whatever its outcome, may well result in even more pandemonium and polarization. This time, NaNoWriMo has a strategy.

“We’re doing scenario-planning, thinking up ways to help people harness their creativity,” Grant says. “It’s a process that started in the earlier days of the pandemic. In late March, we launched #Stay Home WriMo (‘WriMos’ are what participants call themselves), a daily checklist of five activities people can do to take care of themselves emotionally, socially, creatively, mentally while sheltering in place. It got a great response. Using that as a model, we’ll probably keep something like it in mind for November.”

Below, enjoy a deep-dive into the nitty-gritty of NaNoWriMo’s magic. We talked with Grant about how creativity is an “anti-numbing agent,” how kids are great role models for writing without fear, and how no one really writes alone.

BABF: You’ve written about how you “unofficially” did a self-directed NaNoWriMo-esque challenge once, setting yourself a goal of writing 1,500 words a day for one whole summer while you were housesitting. Then, in 2010, you officially participated in NaNoWriMo for the first time. How were those two experiences different: the self-contained approach to writing versus the communal, collective experience NaNoWriMo offers?

GF: I’d actually forgotten about that housesitting summer! But yes, there was a world of difference. Here’s the main one: there’s something tremendously, magically galvanizing about writing essentially with the world. It’s energizing, and the primary gift [NaNoWriMo] gives writers is motivation: you feel like you’re doing something that’s larger than yourself. There’s also a huge accountability factor in announcing your goal, publicly, to so many. When you go to the grocery store, for example, there’s always the chance you’ll see someone who’ll ask you ‘hey, how’s that novel going?’ It’s the good side of peer pressure. And when you’re doing it totally alone, there’s fewer of those gusts of wind that come from others writing with you.

BABF: That community-oriented motivating aspect is an interesting one, especially in light of this prevailing perception that writing is a completely solitary activity. Does NaNoWriMo undercut that belief?

GF: A lot of writers mythologize this idea of doing the work in solitude and anguish. It’s a very American individualist idea of the cowboy, and writers have internalized that too much, to the point where they tend to underestimate what other people give them. Throughout history, writers have always been part of a community: the Beats, the salons in 1920s Paris. And NaNoWriMo emphasizes that conversation that takes place between writers.

You can’t underestimate the power of absorbing the creativity of others. When people are with other writers, in whatever capacity, you’re picking up on their energy. That’s where the creative magic comes in. Studies have actually been done on this—there’s a psychologist, Keith Sawyer, who did a study on “understanding group flow” in fostering creativity, and found that people feed off each other’s creative energy. It’s why so many writers like to write in cafes. You’re not directly interacting, but you’re picking up on the momentum and flow of the people around you.

I like the way one of our volunteers, a New Jersey WriMo named Bill Patterson, put it: “Writing is a solitary activity best done in groups.”

BABF: Another writerly neurosis NaNoWriMo seems to subvert is performance anxiety.

GF: That’s true. We don’t emphasize perfection. It’s not about trying to be the best. It’s about learning and sharing and taking risks. The goal isn’t to produce a perfect finished product. And that can be incredibly liberating, because we’ve got people sharing their worst sentences with each other, not just their best, and laughing about it, and defusing and demystifying that need to impress. It’s a recognition that your worst sentences and your best sentences speak to each other. And that ethos is embraced and runs through all the people who participate in this community. NaNoWriMo is not a top-down organization giving everyone a prescription for “how to write.” It’s the community that makes the climate, not the people running things. That’s one thing that makes the experience so powerful.

BABF: Do you find that this de-emphasizing of perfection is one factor that makes NaNoWriMo so well-suited to kids as well as adults?

GF: Yes, I think kids of all ages are more likely to approach an activity with a sense of playfulness. And that’s something we lose when we grow up. Kids are less likely to worry about being the best ones in the room; they’re very good at creating art for art’s sake. Remember that feeling of being 12 years old and just sitting down to write a story, just to do it? One gift of NaNoWriMo is that it takes us back to that childlike state of having no expectations beyond writing for writing’s sake. That’s what we see in our programs that take place in classrooms. It’s not students writing in a classroom alone; it’s a classroom turning into a writing community. Kids will be on the playground, running up to each other and asking ‘what word count are you up to?’ And it’s just sheer playfulness and joy.

BABF: You mentioned how paralyzed so many writers were in the wake of the 2016 election. Now, we’re mired in another set of extreme circumstances, and we keep hearing how much trouble people are having even reading, let alone writing. How’s your own writing and reading practice been holding up during this time?

GF: I’ve actually taken a lot of refuge in reading and writing lately. I’ve been doing it at the same levels at which I’ve always done it. Typically, my schedule is to get up at 5:30 in the morning and do as much as I can. And I’ve been reading as much as ever. Part of that is having deadlines I have to meet.

But I’ve heard from other writers that they’ve been unable to do it lately. We all have different responses to what’s going on, and there’s no right or wrong way to respond. But one thing that helps motivate me is something I think Toni Morrison said: to paraphrase, the essence of it is “when in despair, create.” You can get on Twitter and doom-scroll to see what’s going on in the world, but the best thing is to doom-scroll and to create. It can help to remember that creating art isn’t a selfish endeavor; it’s the act of telling a story that brings light. Creativity is an anti-numbing agent.

Check out Grant’s website (featuring his blog, published essays, and info on his books), and learn how to be part of this year’s NaNoWriMo here!