The coronavirus has taken the narrative shape away from both students and professors.

-Dan Chiasson, The New Yorker

For this special edition of Literary Sustenance, we’re reflecting on an aspect of our new normal that’s impacting millions: the disruption of higher education.

The closing down of campuses and the transition to distance-learning may seem minor when we compare it to overwhelmed hospitals and massive unemployment, but the eradication of campus life is still a loss, and a complicated one. College isn’t just a place to get a degree; it’s the setting for a formative period of growth, a wellspring for some of the most significant personal and professional relationships of our lives, and a symbolic and literal promise—especially for first-generation and nontraditional students—of a future full of new and different possibilities.

In March, shortly after many cities across the country issued sheltering-in-place recommendations, renowned poet and critic, longtime New Yorker contributor, and Wellesley College English professor Dan Chiasson published a powerfully resonant essay, “The Coronavirus and the Ruptured Narrative of Campus Life,” in The New Yorker. This piece, full of poignant insights about the consequences—emotional, logistical, health-related—of removing students from their regular learning environments, struck a chord with people across the nation, personalizing the impact in a way that hit home:

I keep thinking especially of students who are in love, and who may be in love in ways not permitted in their homes or communities. The person you became infatuated with last Thursday is now suddenly going to be on the other side of the world. I think of students whose identities needed the entirety of spring to play out. What will they face when sent abruptly home? They’d just got started.

We spoke with Dan, below, about the emotional intricacies of teaching poetry and being there for his students in the midst of a semester that’s anything but typical.

In our next blog post, Part II of this reflection on higher education in the midst of COVID-19, we have something we’re especially proud to share with you: personal reflections on this issue from the other side of the lectern (or the Zoom screen, as it were), courtesy of four of our amazing BABF interns. You can find their personal reflections on college life in lockdown here.

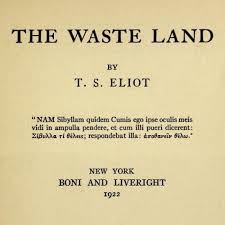

Moleskines, The Waste Land, Meeting Students’ Cats, and Adventures in Zoom: A Conversation with The New Yorker‘s Dan Chiasson

“I threw out the old syllabi and chose poems that speak to interruption.”

BABF: Since you’ve started teaching your poetry courses online, do you find that the narrative trajectory of the class—the progress you’d all made together thus far, and are now trying to build on virtually—has been deeply disrupted? Or are you able to establish a different kind of collective forward motion?

DC: Today [editor’s note: this conversation is from last month] I began our online ZOOM courses, and it was fantastic to hear each others’ voices and to adapt as best we could to the circumstances. I was in our filthy kitchen, but had angled the screen to give a view of the window behind me. It was 6 AM for the students on the West Coast. I met two magnificent cats, and we bonded over the Netflix show Tiger King. Clearly, here was a new experience with its own phenomenology—and though I’m trying to stitch the new reality into the old, the moment calls for some measure of reinvention.

My classes are continuing on three fronts. I started blogs

The ZOOM classes remind us that every situation is different. Some students are disadvantaged by, say, being across the world; others might be down the block but need to care for their little brother all day. Nobody so far that I know of has become ill, but lots of students have parents and loved ones working in ways that put their lives in jeopardy.

BABF: What’s been resonating with your students lately, poetry-wise?

DC: Both of my classes are reading

BABF: You mentioned in the essay that you often synchronize your syllabus to the changes in seasons and light. If you somehow could’ve seen what was coming this spring semester, and were able to remake one of your syllabi in advance to correspond to these circumstances, what do you think you would’ve put on it?

BABF: Do you have any chance to read for pleasure these days? Is there anything in particular that’s been bringing you solace?

DC: I am slowly reading War and Peace,